A Cinematic Exploration in Oppenheimer – Movie Review

Christopher Nolan has always been drawn to big questions: time, memory, morality. And with Oppenheimer, he tackles the biggest one yet, what happens when brilliance gives rise to destruction?

This isn’t just another historical drama; it’s a film that stares directly at the birth of the atomic age and asks us to sit with the discomfort of genius turned catastrophic. Is this one of Nolan’s most ambitious undertakings yet? Absolutely.

Nolan’s Storytelling: Memory as a Puzzle

Nolan doesn’t do straight timelines, and Oppenheimer is no exception. The film unfolds like memory itself, fragmented, looping, sometimes dream-like, sometimes painfully clear. We’re pulled between past, present, and flashes of the inner world of J. Robert Oppenheimer, and it works.

Rather than giving us a standard biopic, Nolan cracks open Oppenheimer’s psyche. The result? A portrait not just of a scientist, but of a man haunted by the very thing that made him famous.

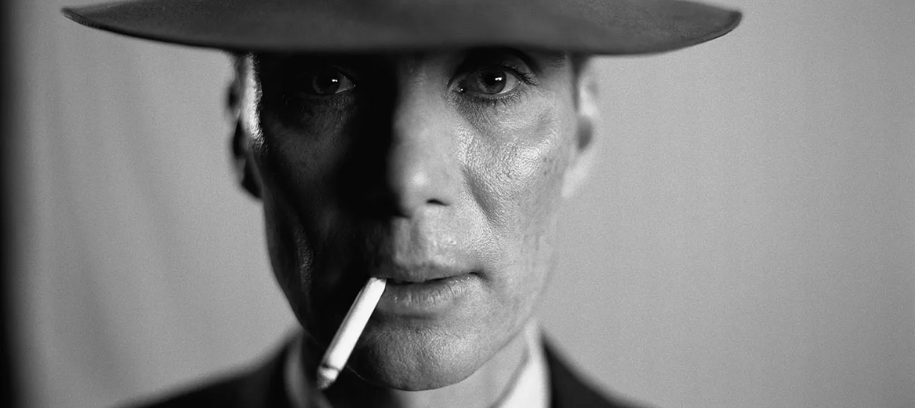

Cillian Murphy’s Quiet Storm

At the core of the film is Cillian Murphy, whose portrayal of Oppenheimer is both intellectual and deeply human. His performance isn’t loud, it’s restrained, filled with quiet intensity that lingers long after the credits. Every hesitation, every flicker of doubt, every flash of arrogance feels lived-in.

The Supporting Firepower

If Murphy is the storm at the center of Oppenheimer, the supporting cast provides the lightning bolts that keep the film charged. The cast is definitely star-studded, and they all delivered above and beyond on the screen.

Emily Blunt, as Kitty Oppenheimer, makes her limited screen time unforgettable, especially in the hearing room, where a simple refusal to shake Strauss’s hand cuts deeper than any outburst. Robert Downey Jr. delivers a career-best as Strauss himself, all ego and bitterness, while Florence Pugh’s brief turn as Jean Tatlock lingers with a haunting weight.

This is Nolan at his best: assembling not just a lead, but an ecosystem of performances that elevate the story into something far greater

Visuals and Sound: Nolan at Full Force

No Nolan film is complete without spectacle, and here he teams up again with cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema. The deserts of New Mexico, the sterile halls of Los Alamos, the blinding light of the bomb tests, every frame feels deliberate, immersive, almost overwhelming.

Ludwig Göransson’s score (yes, not Zimmer this time) collides with the imagery, swelling and receding like a pulse, dragging both awe and dread into the audience’s chest. Discovery and destruction, unfolding hand in hand.

The Moral Fallout

But what really makes Oppenheimer unforgettable isn’t the science or the visuals, it’s the moral weight. The film forces us to confront the uncomfortable: when does scientific progress cross into ethical failure?

Oppenheimer himself becomes the symbol of this paradox. A man celebrated for his genius yet tormented by its consequences.

In South Asia, where the shadow of nuclear weapons has loomed large in politics and security, the story hits differently. It’s not just history; it’s a reminder of the fragile line between innovation and annihilation. It’s less “look what they did” and more “look what we still live under.”

Barbenheimer and the Box Office

Of course, Oppenheimer didn’t drop quietly. It was released head-to-head with Barbie in July 2023, giving birth to the cultural phenomenon we now know as Barbenheimer. While Barbie dazzled pink and pulled in over $1.4 billion globally, Oppenheimer carved its own lane, grossing more than $950 million worldwide. For a three-hour R-rated drama heavy on dialogue and moral dilemmas, that’s not just impressive, it’s historic.

It became Nolan’s third-highest-grossing film ever, behind only The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises. So while Barbie painted the summer in neon, Oppenheimer etched its mark in shadows, and audiences showed up for both.

Why It Matters

Oppenheimer isn’t light, and it’s not supposed to be. It’s dense, unsettling, and demands something of you. But that’s Nolan’s craft, he doesn’t hand you answers, he hands you questions.

And maybe that’s the point. Oppenheimer’s dilemma — “Should we, just because we can?” — isn’t locked in the past. It’s staring us in the face today.