Vincent van Gogh: A Canvas of Emotions, A Chronicle of Life

Vincent van Gogh, a name so familiar it almost feels personal. A man we will never encounter in our lifetime, but has spoken to us through his brushstrokes, each painting a fragment of his inner world.

In this piece, we journey through Van Gogh’s life, tracing his evolution from somber realism to bold, emotional abstraction, and his ascent from genius to madness, all while allowing his art to tell the story.

Humble Beginnings

To start and understand Van Gogh as a whole, we have to look over to a time before the vibrant sunflowers and the swirling night skies. Yes, we first take a look at his early masterpiece, The Potato Eaters, which was received poorly by critics at that time is essential in understanding the humble beginnings that make up the legacy of Van Gogh.

This piece is gritty and unglamorous, with earthy tones, rough textures, and faces carved by hardship. It wasn’t meant to please; it was meant to tell the truth. Van Gogh portrays a peasant family gathered around a dimly lit table, sharing a humble meal. Through a murky palette, his goal was not to paint peasants, but to show empathy. Contemporary literature continues to study the work extensively, with reviews stretching from the interior of the painting to the postures of the peasant. To say the least, while this may not be his most recognized painting, it embodies the soul of who Vincent Van Gogh was.

Sunflowers and Self Portraits

Now, when we time jump into the late 1880s, Van Gogh had moved south, eventually settling in Arles, France, drawn by light, color, and the warmth of the landscape. This relocation was reflected in his iconic Sunflower series.

With its blazing yellows, swirling petals, and bold contrasts, it represents both vitality and vulnerability. What seemed like an explosion of color was, in many ways, Van Gogh’s expression of healing his own wounds. In his letters to his brother Theo, Van Gogh wrote about chasing “the light of the South,” a light he believed could heal him. Works like Sunflowers and The Bedroom from this period are love letters to color itself, bold, spontaneous, alive.

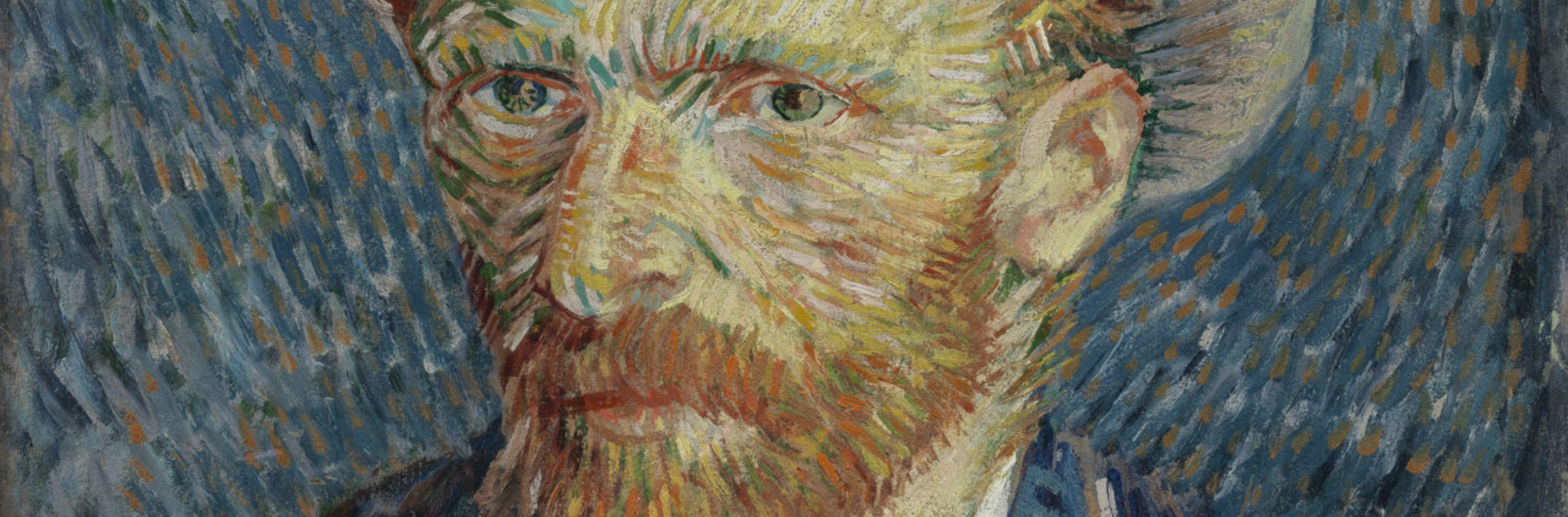

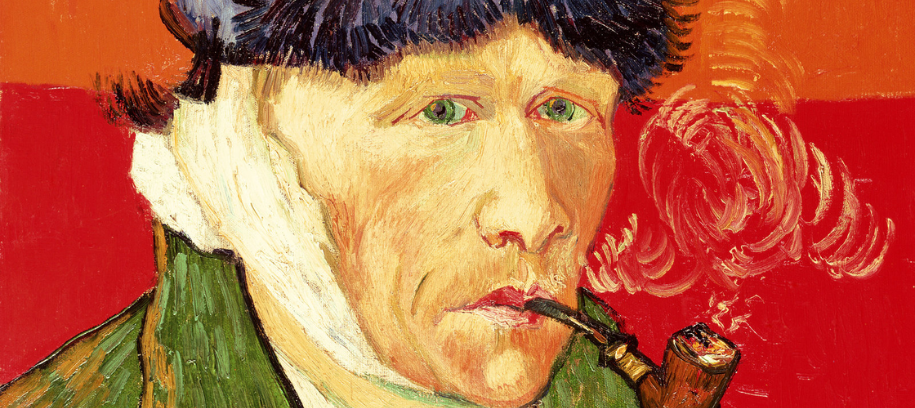

Yet beneath the beauty, there’s always a tremor, a reminder that his genius was constantly shadowed by mental turmoil. This turmoil is often depicted through his self-portraits, revealing an artist wrestling with the reflection staring back at him: confident, unstable, hopeful, haunted. The one that continues to spark the most conversation is his, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear (1889)

When the Night Spoke Back

By 1889, Van Gogh had admitted himself to the asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, following a breakdown that has been the center of myths for generations. And, from that quiet room came The Starry Night — perhaps the most recognized painting in the world.

As described by the Guggenheim Museum, it’s a cosmic symphony of emotion: stars like beating hearts, a sky that refuses to sit still, and a village that sleeps beneath a restless heaven. It wasn’t astronomy; rather, it was autobiography. Every swirl is Van Gogh translating his inner storm into motion.

Even his softer works from this period, like Irises and Almond Blossom, radiate hope. As if, even in confinement, he was still reaching for sunlight. “I don’t know anything with certainty,” he once said, “but the sight of the stars makes me dream.” Maybe that’s what The Starry Night really is, not madness, but hope and dreams translate onto a blank canvas.

Why Van Gogh Resonates Today

Van Gogh’s genius lies not just in his brush, but in his audacity to paint pain, to make melancholy beautiful, and to transform personal chaos into universal art. Here’s what continues to speak to those who cherish his art in the 21st century:

- Emotional transparency: Few artists have bared their inner storms so openly.

- Color as language: He experimented with color not just to represent, but to feel.

- The human struggle: Even in manic creativity, he never lost sight of suffering, hope, and dignity.

Vincent van Gogh died in 1890, having sold only one painting in his lifetime. But time, as it turns out, is the greatest curator.